Late twentieth century media, the sexual liberation of women, led to the rise of the female spectator. This resulted in a conflict of values: men were not traditionally supposed to be viewed as sexual objects, and yet women wanted to desire them sexually. Hence, Star Trek sought to enhance Kirk’s sex appeal, and to encourage female spectatorship, without overtly presenting Kirk as sexually-motivated.

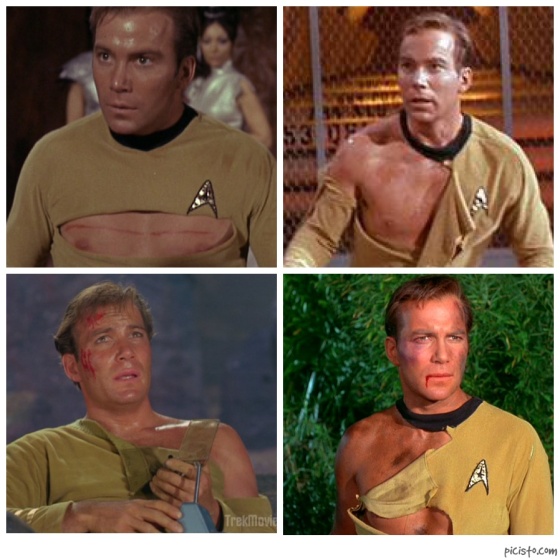

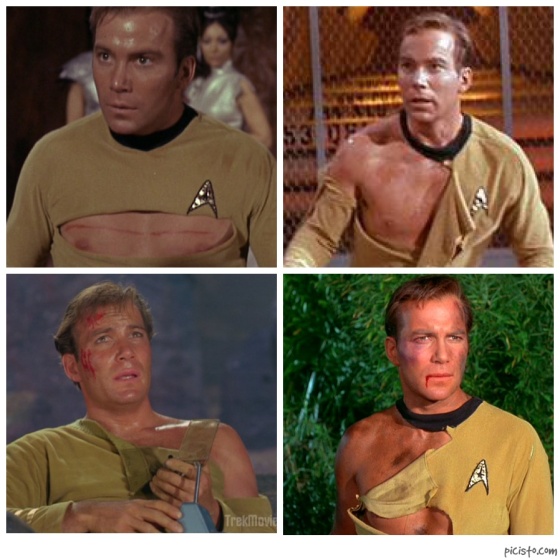

Captain Kirk and his various ripped shirts. Semi-nudity is imposed on Kirk during acts of violence.

At the time that Star Trek’s original series first aired (1966-1969), there was not much discussion about the meaning of male nudity, nor the female spectator. It is only in more recent decades that theorists such as Laura Mulvey have begun to explore the difference between the meaning of male and female nudity, and the gendered gaze, and how things were shifting as a result of the move towards sexual equality.

There were several key problems facing Star Trek screenwriters who want to give audiences a glimpse of male flesh. Perhaps the most pertinent of these was that the 1960s, and hence the fictional future as depicted in the Star Trek original series, was patriarchal. Peter Lehman argues that “avoiding the sexual representation of the male body… works to support patriarchy” [1]. Male characters, particularly Kirk (as leader), had to remain authoritative and masculine. As Laura Mulvey observed, “the male figure cannot bear the burden of sexual objectification” [2]. A man who voluntarily disrobes with the intention of displaying himself as the subject of sexual desire can be viewed as vain. Vanity is historically viewed as a feminine trait, and thus the male striptease can compromise masculinity.

Additionally, the naked male body can be viewed as “threatening” to the female audience, since voluntary exhibitionism is closely linked to sexual aggression[3]. It is noteworthy that Kirk was often shown as sexually reluctant – the victim of sexual desire rather than the perpetrator.

James T. Kirk could not, therefore, be seen to exhibit his body intentionally. Rather, nudity had to be imposed upon him. It could be incidental, accidental, or justified for practical (and manly) reasons, but never purposeful.

Even when Kirk has voluntarily removed his shirt, it is often to engage in masculine acts of violence and displays of physical strength.

Kirk’s semi-nudity was made more acceptable by being shown as the consequence of masculine aggression. A violent tussle with enemy foe could be the cause of a ripped shirt, and hence an exposed nipple. Kirk’s toughness could be reinforced by a splatter of blood or sweat on the exposed skin. In hand-to-hand combat, Kirk could progress towards nudity without appearing to voluntarily expose himself to the audience. He satisfied the sexual urges of some audience members, without compromising the masculine values that mattered to the remaining viewers.

Kirk was thus positioned as the heroic nude, or the athletic nude, comparable to the characters depicted in cultural artefacts of Ancient Greece (and, of course, their thinly veiled homoeroticism). His sculptural semi-nudity connotes heroism, strength, and agility.

Pierre Brule, in his observations of Ancient Greek athletic nudes, noted that “nudity was the distinctive mark of being both male and Greek, since neither Barbarians nor women exercised naked” [4]. Parallels can be drawn between Ancient Greek’s approach to Barbarians, and Star Fleet’s approach to uncivilised alien societies. In this context, Kirk’s semi-nudity is a sign not only of his masculinity, but also his humanity. His bare chest, with smooth pink skin, is evidence of his status as human, in contrast to the assorted blues and greens of his alien combatants.

In hand-to-hand combat, there is also a descent into savagery. In times of foreign exploration, explorers who have encountered tribes who wear little or no clothing have often been assumed to be primitive “savages” [5]. Their nakedness was thought to be a reliable indicator that such groups of people were under-developed, having not yet developed the intellectual capacity for morality, and hence for the ideas that nakedness is shameful. Among European and American slave traders, nudity was enforced to keep perceived savages in their place; as a sign of their status as possessions – equivalent to animals such as cattle – rather than humans. In Kirk’s own descent towards savagery, he must abandon the civilised negotiation techniques of Starfleet. As the uniform is ripped, Starfleet’s regulations and values and tossed aside. Kirk becomes a beast that cannot be tamed by the authority and civility of his employers.

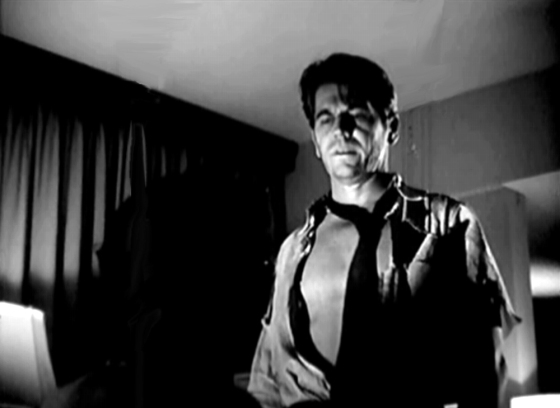

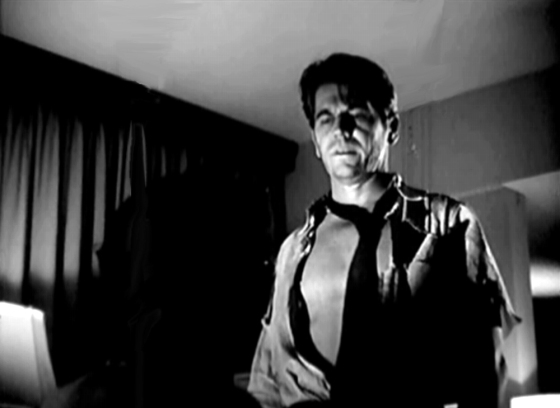

Star Trek was by no means pioneering in its use of the ripped shirt. There are numerous films and TV series that depicted men in similar semi-nude states, always imposed by masculine acts of action or violence. Take, for example, The Most Dangerous Man Alive (1961), in which Eddie’s shirt is ripped to shreds in an explosion. Here, though the shirt is torn and Eddi’e chest is fully exposed, his tie remains intact to retain some sense of respectability and civility.

In The Most Dangerous Man Alive (1961), Eddie’s shirt is shredded in an explosion.

As if his skintight superhero costume wasn’t enough to please flesh-hungry audiences, Captain America 2: Death Too Soon (1979) depicts Steve Rogers with a ripped shirt.

Other sci-fi and fantasy tales find similar excuses to expose the bodies of their male heroes. For characters including The Hulk (aka Bruce Banner), or numerous werewolf tales (Buffy’s Oz, Being Human’s George Sands, etc.) the loss of a shirt is a clear indicator of descent into savagery. The civilised human identity transforms into the primal/animal identity, and during this descent vestiges of civility and advancement are destroyed. With these werewolf tales, as with Kirk, the nudity is imposed, not performed. It is a consequence of the violent transformation that characterises the curse. The male body becomes the victim of nudity.

In the US remake of Being Human, werewolf Josh Levison wakes naked, next to the deer that he has slaughtered as a wolf. The bloodstains on his naked body, and the similarity between his state and the dead deer that lies beside him, suggest that he is both perpetrator and victim of violence. While naked, he is both savage and vulnerable.

Nudity gives these characters a particular vulnerability when they transform back into human form. The human alter-ago is often meek: the polar opposite of his beastly counterpart. This is particularly true of Buffy’s Oz, and the Hulk in Joss Whedon’s Avengers Assemble. As Bruce Banner has lost his clothes in his transformation from human to beast, when he reverts to his human form he is left without protection from cold or the prying eyes of curious onlookers. He is forced to hide, or make do with borrowed or stolen coverings. Nudity thus reinforces the vulnerability of man, in contrast to beast.

Promos depict the latest incarnation of ‘Teen Wolf’ with his shirt ripped during transformation.

Though Kirk’s imposed nudity was a fairly regular occurrence, more recent sub-genres of sci-fi and fantasy have exploited it to such an extent that it has become a defining feature. Promotional materials for MTV’s Teen Wolf unashamedly permit voyeurism in their teenage audience, with images depicting a naked torso beneath ripped shirt: an image that has come to signify a recent transition from man to beast, and vice versa.

References:

[1] Lehman, Peter, Running Scared: Masculinity and the Representation of the Male Body, Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1993, p. 6.

[2] Mulvey, laura, ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, Screen Vol. 16. Issue 3 (Autumn 1975) p. 12.

[3] Cooper, Emmanuel, Fully Exposed: The Male Nude in Photography, Oxon: Routledge, 1990, p. 8; and Tejirian, Edward Male to Male: Sexual Feeling Across the Boundaries of Identity, New York: Routledge, 2000.

[4] cited in Moss, Rachel E., ‘An Orchard, A Love Letter and Three Bastards: The Formation of Adult male Identity in Fifteenth Century Family’, in What is Masculinity? John H. Arnold, Sean Brady (eds), New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2001, p. 231.

[5] Perniola, Mario, ‘Between Clothing and Nudity’, 1989, as cited in Barcan, Ruth, Nudity: A Cultural Anatomy, 2009.