The Guardian posted a curious news story yesterday, describing a recent burglary attempt in Italy. A group of men broke into a designer clothes shop, and were later caught “standing stock still in a display, trying to pass themselves off as shop dummies.”

What is perhaps most remarkable is the men’s age. Both were in their seventies – well past their physical prime – and yet it was not their physical form that was their undoing. Indeed, the arresting officer claimed that “dressed in jacket and tie, the two men were almost elegant enough to pass for the mannequins they stood alongside.” The men only gave themselves away by their inability to stand still without “trembling “[1].

Typically, mannequins are not representative of a shop’s clients, and even less so its burglars. They are idealized forms, representing the clients aspirations. Mannequins are necessarily idealised, because fashion is not about reality. It is about ambition. Underpinning fashion is the desire to imitate “social elites by their social inferiors”[2]. Designers and retailers present the consumer with a fantasy, encouraging them to imagine themselves as someone better: wealthier, and more successful; slimmer and more attractive.

If these burglars were able to masquerade convincingly as mannequins, even for a moment, does it suggest that the shop’s display had an unusual level of realism? Or, does this story tell us less about the shop display, and more about the arresting officer who was momentarily convinced by the burglars’ disguise? This officer saw two elderly men in the context of a window display without realising that looked out of place. For some reason, he was unable to tell realism from idealism.

Mannequins have an interesting historical relationship with realism. “Dress cannot be understood without reference to the body”[3], and so seeing a garment hanging limp on a peg is insufficient to demonstrate its potential. Clothes are designed to dress the body, and their purpose is unfulfilled if they are not worn. For this reason, when clothing is displayed it is commonly displayed on a human body, or on an artificial substitute for a body, such as a mannequin. Initially, models and mannequins were introduced to show consumers how a garment would look on their own bodies. Realism was therefore considered vital.

In the 1920s, when Jean Patou began using live models, he aimed to employ women that not only showed the clothes well, but also to provide a means by which his customers could “identify more easily with his designs”. Other designers of the same era continued to use models with this goal in mind, selecting models whose shapes reflected the audience, including short or stocky women. In short, the ideal model at this time was deemed to be one who was “ordinary”, emphasizing the “accessibility” of the garments. Catwalk shows thereby aimed to show audiences reflections of themselves, in models to whom they could relate [4]. Similarly, mannequins were designed to be as lifelike as possible [5].

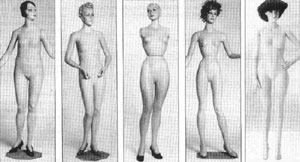

Christian Dior’s New Look of 1947 dramatically changed the modelling industry. The New Look prioritized glamour and extravagance over practicality, and so the models were chosen to reflect this ideal. Dior’s models did not reflect the consumer, but who she aspired to be. They were groomed, sophisticated, and confident [6]. The model became a symbol of an ideal woman and lifestyle. By the 1950s, Dior’s methods had been adopted by mannequin designers. Mannequins became idealised. Male mannequins became muscular and tall, and women’s mannequins became slender, with impossibly long legs and narrow waists. This trend stayed with mannequins, which still today reflect an impossible ideal rather than a reality [7].

Although it has been sixty years since this shift took place, there still exists a level of self-denial about the level of realism in fashion displays. Consumers are easily persuaded to make purchases after viewing a garment on a mannequin, no matter how dissimilar the mannequin’s form is to their own body. This blurring of reality and idealism is the central theme of Michael Gotleib’s 1998 film, Mannequin. The film tells the story of a window-dresser whose muse is a mannequin brought-to-life.

The role of Emmy, the titular mannequin, is played by Kim Cattrall and a series of fibreglass imitations of the actress. With her astonishing beauty, Cattrall is able to convince audiences that she could pose as a mannequin. Notably, her character is not just an ordinary girl but an ancient princess who has harnessed magic to travel through time. It would seem that the impossibly slender form and flawless beauty of a mannequin is only fit for royalty. We could not imagine a plain and ordinary girl in this role. And yet, the very fact that this fantasy exists, suggests that audiences crave the idealism of a window display to be reflected in the reality of their everyday lives or flawed bodies.

Two aging burglars, apparently inconspicuous alongside the chiselled fibreglass forms of male mannequins, tell us that we still believe mannequins are reflective of reality. Advertisers and retailers have been successful in trying to convince us that their artificially idealised vision could come true. One Italian officer, at least, is so influenced by the pretence of reality that he is unable to tell the real from the ideal. For him, the retailer’s vision is convincing. The burglars too, were so confident in the achievability of the retailer’s display that they believed themselves able to replicate it. Mannequins may be idealised, but we are in such denial that we fail to recognise when a real form infiltrates a display. We still believe that, if we buy those overpriced designer garments, we could look as good as the mannequin as the shop window.

[1] Klington, Tom (2012), ‘ Dumb and dummies: Italian trio held over shop break-in,’ The Guardian [online], 17 Dec 2012, http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2012/dec/17/shop-dummy-italian-thieves-arrested

[2] Crane, Diana (2000), Fashion and its Social Agendas, London: University of Chicago Press, p. 6

[3] Joanne Entwistle, cited in Perthuis, Karen de (2005) ‘The Synthetic Ideal: the Fashion Model and Photographic Manipulation’, Fashion Theory 9 (4), p. 410.

[4] Soley-Beltran, Patricia (2004), ‘Modelling Femininity’, European Journal of Women’s Studies 11 (3), p. 311.

[5] Dwyer, Gary, (2008), Window Dressing: Idealized women in the age of mannequins and photography, Lulu, p. 4.

[6] Soley-Beltran, Patricia (2004), ‘Modelling Femininity’, European Journal of Women’s Studies 11 (3), pp. 311-312.

[7] Dywer, p. 11.

Images:

Male mannequins: http://www.myglassesandme.co.uk/2012/04/currently-showing-at-zara/

Mannequins through the ages: http://www.csuchico.edu/pub/inside/archive/02_12_12/05_deadly.html

Mannequin movie still: http://www.allmovie.com/movie/mannequin-v31327