In fiction, a costume so often becomes inseparable from a character. Any visual medium (illustration, film, etc.) has the potential to permanently etch a connection between a character and her costume. When that vision is pervasive, as with Disney, the character and costume become so inseparable that other, existing depictions seem somehow inauthentic. Disney’s Snow White, in her puffed sleeves and yellow skirt, is now the overarching vision of the character, and contemporary illustrations are often forced to retain some features of that garment in order to maintain faithful to audience’s expectations.

Disney’s pervasive vision of Snow White is the model on which numerous others are based. Any images which avoid this inspiration are perceived as being inaccurate.

But it is not just in images that fairy-tale characters have been defined by their clothes. Fairy tales have a habit of reducing characters to stereotypes, identifying one or two core features, visual or otherwise, to mark characters apart. Female characters are sometimes reduced to item of clothing. In some tales, the costume either defines (Red Riding Hood) or overtakes (Red Shoes) the identity of the girl who wears them.

Red Riding Hood’s real name is never revealed in Grimm’s version of the tale. She is defined entirely by her clothes.

Red Riding Hood’s identity is so bound up in her clothes that we never learn her real name:

Once [the grandmother] made her a little hood of red velvet. It was so becoming to her that the girl wanted to wear it all the time, and so she came to be called Little Red Riding Hood. [1]

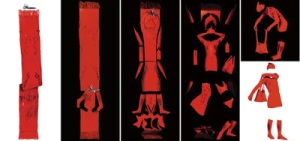

Her identity is so bound up in her costume that the cape has become the sole signifier of the character.

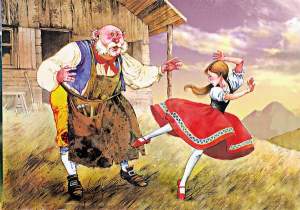

Clothes play a central role in this fairy tale, and identities (real or apparent) are bound up in clothes throughout. When the wolf adopts the identity of the grandmother, he does so by dressing up in her bedclothes. Although the grandmother is given an identity beyond her clothes, it is this part of her that the wolf uses to apparently become her. The disguise is so convincing that Red Riding Hood does not recognise the figure as a wolf.

In a version of the tale recorded in 19th century France, Little Red Riding Hood performs a striptease in front of the wolf [2]. Red Riding Hood is depicted as a seductress, and even where this incident is missing from the tale, much has been made of the connotations of the red hood, equating it with sin and passion [3]. To reduce the character’s identity to that of her clothes, is to deny her all other aspects of character that are not signified by the red cloth. She is primarily, and completely, the sinner or seductress that is implied by her garment.

In a lesser-known story of the brothers Grimm, Furrypelts, a princess is named for the cloak of “thousands of kinds of pelts and furs” that she uses to conceal her beauty [4]. In the more familiar tale of Red Shoes, a girl becomes possessed by her shoes in punishment for her vanity. Both of these tales begin with the assumption that young women have a frivolous desire for extravagant fashion, and the connection between clothes and femininity is central to many other tales, including Cinderella. This is a theme that I will investigate in a further post, so watch this space!

In Hans Christian Andersen’s tale, a pair of Red Shoes possess a girl’s feet until she is forced to cut them off with an axe.

References:

[1] Brothers Grimm, ‘Little Red Riding Hood’, reproduced in Tatar, Maria, The Annotated Brothers Grimm, New York: Norton, 2004.

[2] Tatar, Maria, The Annotated Brothers Grimm, New York: Norton, 2004, p. 141

[3] Bettleheim, Bruno, ‘Little Red Cap and the Pubertal Girl,’ in Dundes, Alan (ed.), Little Red Riding Hood: a Casebook, London: University of Wisconsin Press, 1989, p. 286

Images:

Disney’s Snow White: http://g-ecx.images-amazon.com/images/G/01/dvd/Disney/Images/SnowWhite6.gif

Red Riding Hood: http://3.bp.blogspot.com/_FvmCyKhrGrg/TCrNxbQZy3I/AAAAAAAAAac/RsQQHDBAu0c/s1600/411px-Little_Red_Riding_Hood_-_Project_Gutenberg_etext_19993.jpg

The wolf dressed in grandmother’s bedclothes: http://4.bp.blogspot.com/-9r0C2oxNj3U/Ty42FhxoKGI/AAAAAAAAD84/R4ZZuzGCiMY/s1600/Doré+Little+Red+Riding+Hood.jpg

Furrypelts: http://25.media.tumblr.com/tumblr_ma7lynnC2g1qkevp7o1_500.jpg and http://a4.ec-images.myspacecdn.com/images01/109/2f30a03e2527e3e040cd8a8276e514d7/l.png

The Red Shoes: http://www.johnpatience.co/hans-andersen/