Earlier this year, the FSB expelled an America diplomat on the grounds that he was spying for the CIA. Listed the alleged spy’s suspicious possessions including, rather cryptically, “means of altering appearance”. It was later revealed that this disguise kit contained a variety of wigs and sunglasses. These paraphernalia were so ill-fitting that they belonged in a comedy performance, but they provoked some serious debate.

Speaking on Radio 4’s Today programme, former CIA operative, Robert Baer, admitted that although wigs are “not common practice”, he and his colleagues had worn thick-rimmed glasses and stick-on moustaches to break up facial contours. The aim of these disguises was to make people remember “something other than the face”[1]. The face is the focus of disguise for criminals as well as spies. With varying success, criminals mask their faces with tools ranging from typical balaclavas, to adventurous prosthetics, and ludicrous marker-pen camouflage. One of the most commonly depicted burglar’s disguises is a makeshift mask of a stocking pulled over the head, which succeeds in distorting (rather than concealing) the wearer’s features.

The owner of the ‘Armed Robbery Advice’ website demonstrates how a stocking pulled tightly across the face can distort facial features, transforming familiar faces into anonymous ones.

Identity and the Face

The face is the key in visual identification, and is a sign of self. Numerous cultural practices of representation reveal that ‘humans predominantly recognize and differentiate others by the face’[4]. Images of the face have historically been, and continue to be, a common method of distinguishing one individual from another, and proof of individual identity. When state organisations and institutions first began to keep photographic records of populations (as when immigration services first issued passports) ‘the face… was deemed sufficiently indicative of the person’s likeness to serve as its overt sign; thus, the rest of the body could be omitted’[5]. Along with criminal photofits, photo IDs and driving licences, these documents helped to establish national and international databases of faces. These, combined with the ubiquity of CCTV and camera phones, have greatly increased the chances of an individual being facially recognised if he or she commits an illegal or remarkable act.

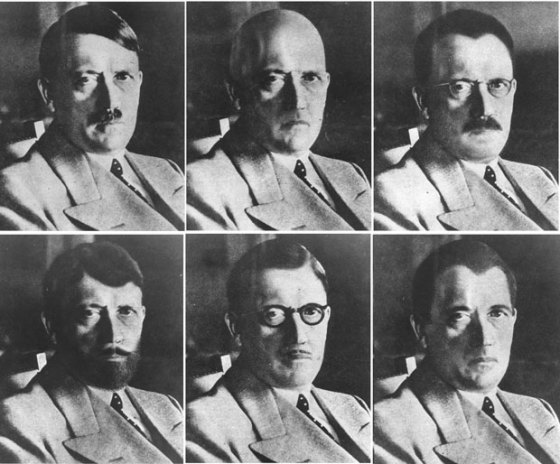

As photographic images because more widespread, and the risk of recognition increased, facial disguise became more necessary. In order to reduce the effectiveness of facial disguises, authorities may produce impressions of wanted men in a variety of possible disguises. In 1944, the U.S. Office of Strategic Services manipulated photographs of Adolf Hitler, to prepare for the possibility that he may adopt a disguise. In these images, Hitler was depicted with glasses, a false beard, false hairline, and a number of other facial obstructions or distortions that would have made him less recognisable. The images had the effect of focusing viewer’s attention on the less distinct features of Hitler’s face. With the moustache and hairline concealed, viewers were forced to concentrate on the subject’s eyes, eyebrows, and nose, and hence to become familiar with these features. Repeat viewing would train viewers to associate these features with Hitler, and so be more prepared to easily identify him should he adopt almost any disguise.

Images created by Eddie Senz for the Office of Strategic Services in 1944, depicting Hitler is a variety of imagined disguised. Source: The Telegraph

In representation and in reality, the face is commonly seen as a sign not only of identity but also of personality. Physiognomy – the belief, originally derived from Aristotle and presented much later as a science by J. C. Lavater and others – that one’s character is presented in the appearance of the face, or ‘the corresponding analogy between the conformation of the features and the ruling passions of the mind’[6]. The face is also an expressive site for our emotions and intentions. It transmits a language of social signals. It is our most expressive body part, and it is possible to read someone’s intentions and motivations through facial expression. It is for this reason that many portraits are expressive, attempting to capture the ‘character’ of the subject, and in particular why criminals may be depicted with a scowl.

Given that a person’s identity, character and intentions are apparently so bound up in the face, it is reasonable for the face to be the cornerstone of disguise. A mask, or any disguise that conceals the face, also in turn conceals identity and intentions.

Failed Iowa burglars, Matthew Nelly and Joey Miller, were caught attempting to break into a flat wearing facial camouflage of permanent marker. In principle, their plans to conceal their faces might have worked, but in practice this technique neither distorts nor conceals the features, and hence the identity, of the men.

Masks as Disguises

Anthropological studies suggest that the mask may represent two different approaches to identity. The first ‘assumes the authenticity of the self’[7]. In such cases, the mask is a lie, concealing the true identity of the wearer. The second approach proposes that the mask presents an aspect of the self. To some extent, ‘the mask reveals the identity’[8]. Identity is complex, and the mask is an ‘authentic manifestation’ of a part of that complex whole [9].

The criminal’s mask may fall into either of these two categories. It may allow the wearer to escape from his own moral values, or to embrace a criminal part of himself that is otherwise repressed. In the first, the mask provides a ‘shield from one’s own morality’[10]. Chad Engelland observes how, ‘by concealing the face, the mask establishes a character who speaks with words of his own’[11]. The mask thus removes responsibility from the wearer for the things he says and does. It removes the connection between an individual and his/her crimes, and hence provides an opportunity to distance him/herself from actions that might otherwise provoke feelings of guilt or fear. The mask becomes a vital tool in de-individuation, by ‘removing personal identification’ and consequently also removing ‘personal responsibility’[12]. The mask is used for similar purposes elsewhere, in less sinister scenarios. In the notorious masquerade balls of the eighteenth century, the mask enabled escape from moral integrity[13]. For children in Halloween costume, it absolves them of responsibility for their acts of vandalism.

Conversely, the mask may reveal the true nature of the wearer, allowing him or her to release the criminal tendencies that are ordinarily repressed. Like all dress, which is a ‘vehicle that announces one’s identity to others’, the mask focuses attention on one aspect of his personality. Rather than deny the identity of the wearer, the mask emphasizes his/her potential for criminality or immorality. That ‘authentic’ aspect of self is brought to the fore through the characteristics of the mask.

Incomplete Identities – The problem with Masks

The problem with the anonymity provided by masks is that it provokes curiosity. The mask is ‘known to have no inside’[15]. It is this sense of an incomplete identity that drives audiences to seek out the secret alternative identity hidden underneath a reductionist or obvious mask, such as a balaclava. The observer knows that the mask is only a surface decoration; superficial, and not representative of a complete identity, which ‘invit[es] the audience to peer behind the mask’[16]. The mask inevitably creates the impression that there is more to be discovered, and encourages the urge to solve that mystery.

The anonymous mask also unsettles observers, provoking an instinctive ‘fear reaction’. Tthis fear is prompted by the concealment of facial expressions, making it impossible to read the wearer’s intentions and hence ‘to predict the behaviour of the masked man or woman’. The ‘inability to predict makes us feel insecure… because we assume – often with good reason – that the masked person is disguised for nefarious purposes’[17]. This fear ‘sharpens scrutiny’, ensuring that the wearer will attract more unwanted attention than if he or she had committed his crime unmasked.

Furthermore, the mere act of wearing an obvious mask may itself be considered morally questionable, as it is a deception of sorts. The ‘mask has come to connote something disingenuous, something false’[18]. The mask is, ultimately, a lie. The word ‘mask’ ‘suggest[s] concealment or deceit, either of the face or person, or of emotions or intentions’[19]. As a disguise, worn with the aim of providing anonymity to the wearer, the mask suggests a ‘sinister dimension’[20]. ‘From medieval times onward, the prevalent interpretation of the mask focuses on its role as an evil disguise’. It has historically been believed that, in masquerade, ‘we… act disingenuously’ and in doing so ‘risk identification with the devil’[21]. An anonymous mask therefore has the potential not only to attract unwanted attention, but also to mark the wearer out as a villain.

The Advantages of Pseudonomy over Anonymity

While many criminals seek to anonymise themselves through disguise, others turn to prosthesis to supplement one identity for another. In October 2010, an unnamed Hong Kong man illegally boarded a flight to Vancouver, wearing a prosthetic mask and carrying the passport of a 55-year old American (see fig. 3). The disguise was so convincing that the man’s true identity was only revealed when he emerged from the on-board toilet apparently 30-years younger. In the same year, a prosthetic mask was worn by a serial robber in Cincinnati, and was so effective as a disguise that police arrested a suspect who looked like the mask rather than the man who wore it. The so called, ‘Geezer Bandit’ who has robbed sixteen banks in California since 2009 was originally thought to be an elderly man. One of the FBI’s recent line of enquiries proposes that the culprit may be a much younger man or woman, wearing a silicone mask designed by SPFX, a Hollywood prosthetics company.

This unnamed passenger illegally boarded a plane from Hong Kong to Vancouver wearing a prosthetic mask. In mask (left) the man assumed the identity of a 55 year-old American.

Unlike an obvious mask such as a balaclava, which provides anonymity to the wearer, prosthetics seem to present a genuine and complete identity. By substituting one (genuine) identity for another (false) identity, they are not easily read as disguises. Robert Barron, who spent more than 30 years as a ‘disguise specialist’ for the CIA, operated with the knowledge that the ‘lives [of CIA officers] were in jeopardy if the disguise attracted attention’[22]. Key to its effectiveness was that the disguise did not give itself away as such. The disguise must be a simulacrum. It must reliably resemble a real face, not a mask. It must apparently present an identity that is so complete that no questions are left unanswered in its appearance.

If such a disguise is associated with a complete identity, that identity can be sustained indefinitely. It is not necessarily a quick fix for a single crime, rather a complete alternative identity and a lifestyle to match. In such incidences of sustained disguise, the second identity becomes a performance that extends beyond the mask. ‘Layers and systems of secrecy’ are constructed and performed to supplement the visual disguise[23]. Pseudonymous disguises therefore require more than just a mask; they require additional props and performance.

Whether a mask provides anonymity or pseudonymity is not necessarily dependent on the properties of the mask itself, rather the context. A mask that is initially effective in establishing an apparently complete alternative identity may suddenly shift in its meaning when an observer identifies it as a mask. In the case of the ‘Geezer Bandit’ a silicone mask provided an alternative identity only until the FBI posed the suggestion that there may be a younger culprit hidden underneath. After this suggestion there was a significant increase in media attention as the case was elevated from crime to mystery.

As it conceals or distorts the face, a mask may be effective at concealing the wearer’s identity. Though the mask is effective at concealing identity, it also draws attention to the wearer, and arouses suspicion over his intentions. The anonymity granted by abstracted, concealed or distorted identity invites unwanted scrutiny from observers. A mask which behaves as a pseudonym, creating a complete but false alternative identity, provides the safety of concealment without inviting questions about what or who is hidden underneath.

This is an abridged version of a paper that I will be presenting at CULTHIST’13 in Istanbul, 23-25 October 2013. The full paper is entitled “‘Anything but the face’: The mask as strength and vulnerability in disguise and identity deception”, and will be available (in text and video) after the conference.

References:

[1] Today, BBC Radio 4, 15 May 2013.

[2] ‘Burqa gang stole watches worth £1m from Selfridges,’ The Guardian [online], 8 June 2013, http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk/2013/jun/08/burqa-gang-watches-selfridges

[3] Kövecses, Z., and Koller, B., 2006. Language, Mind, And Culture: A Practical Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 10.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Brilliant, R., 1991. Portraiture. London: Reaction Books, p.41.

[6] Lavater, J. C., 1826 [1797]. Physiognomy; or The Corresponding Analogy Between the Conformation of the Features and the Ruling passions of the Mind. London: T. Tegg.

[7] Tseelon, E., 2001. Reflections of Mask and Carnival. In: Masquerade and Identities: Essays on Gender, Sexuality and Marginality, London: Routledge, p. 25.

[8] South, J.B., 2005. Barbara Gordon and Moral Perfectionism. In T. Morris, and M. Morris eds. Superheroes and Philosophy. Peru, IL: Carus, p. 148

[9] Op Cit. [7].

[10] Davies, C., 2001. Stigma, uncertain identity and skill in disguise. In: E. Tseëlon, ed., Masquerade and Identities: Essays on Gender, Sexuality, and Marginality. London: Routledge, p.31.

[11] Engelland, C., 2010. Unmasking the Person. International Philosophical Quarterly 50(4), p.447.

[12] Op Cit. [10]

[13] Castle, T., 1986. Masquerade and Civilization: The Carnivalesque in Eighteenth-Century English Culture and Fiction. London: Methuen, p.2.

[14] Miller, K., Jasper, C. R., and Hill, D. R., 1991. Costume and the Perception of Identity and Role. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 72(3), p.808.

[15] Jones, 1971 cited in Napier, A. D., 1986. Masks, Transformation, and Paradox. Berkley: University of California Press, p.9.

[16] Ibid.

[17] MacInaugh, E. A., 1984. Disguise Techniques: Fool All of the People Some of the Time. Boulder, Colorado: Paladin, p. 26.

[18] Napier, A. D., 1986. Masks, Transformation, and Paradox. Berkley: University of California Press, p.xxiii.

[19] Wilsher, T., 2007. The Mask Handbook, Oxon: Routledge, p. 12.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Napier, A. D., 1986. Masks, Transformation, and Paradox. Berkley: University of California Press, pp. 9, 15.

[22] CIA, 2008. The People of the CIA: Robert Barron. Central Intelligence Agency.

[23]Lash, M., 2013. Brilliant Disguise: Masks and Other Transformations, Contemporary Arts Centre New Orleans.