Yesterday’s post introduced Lucy Orta’s ‘Nexus Architecture’, a shared garment which forces wearers to behave as a single unit. A more whimsical artefact with similar consequences for the wearers is Aamu Song and Johan Olin’s Tanssitossut (‘Dance Shoes for Father and Daughter’, 2006). These red felt shoes resemble traditional Finnish boots, with a second, smaller pair attached above. The shoes are intended to be worn by ‘a father and young daughter… together’, with the father filling the main part of the shoes, and the daughter standing on top[1]. These shoes force the wearers into a traditional couples’ dance position, with both wearers facing one another and one wearer, the father, taking the lead.

With his feet in the main part of the shoes, the father has contact with the floor and is therefore able to control the direction and pace of travel/dance. This position reinforces the control that the father already has over his daughter, placing him in a dominant position. Moreover, the instability caused by the daughter’s pose requires the father to support her further by holding her hands, thereby further reinforcing the traditional supportive role of the father. In this pose, the wearers are forced into a choreographed routine. The father’s movements must be mirrored by those of the daughter, who is forced to follow his lead as her feet are firmly attached to his.

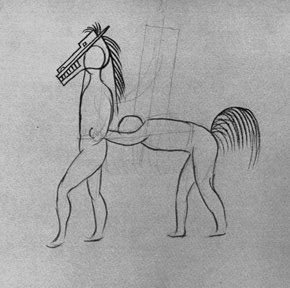

We can return, once again to the pantomime horse. Here, the wearer at the head has control of direction. The wearer at the hind legs is essentially ‘along for the ride’, forced into a subservient position. These garments not only assert relationships between wearers, but make that relationship inescapable by physically binding bodies together. By linking or binding bodies, shared costumes restrict movement, and ensure choreographed motion, forcing the wearers to move as one.

Like many other garments, Song and Olin’s shoes assert identity by highlighting relationships to others. The role of the man, as a father, is asserted by the physical bond to his daughter. Likewise, the identity of the girl as a daughter is communicated in the physical bond to her father. However, it is important to note that these roles are dictated not entirely by the shoes, but by the name given by their creators. These shoes could, in practice, be worn by any couple whose feet differ significantly in size. They could, for example, be worn by mother and son. It is only because the creators’ have labelled them as ‘dance shoes for father and daughter’ that they reinforce the traditional familial and gender roles.

[1] Aamu Song, ‘Tanssitoussut’, Sauma [Design as Cultural Interface], http://www.saumadesign.net/danceshoes.htm

Images:

Tanssitoussut : http://www.incrediblethings.com/kids/dance-shoes-for-the-father-and-daughter/